This guest post by Ben Worthy originally appeared on the Open Data Study .

In July this year the BBC, with a bang and probably a muffled whimper, released details of its highest earners. It predictably provoked outrage at the overpaid but also, less predictably, re-ignited the debate on the gender pay gap. Political leaders were quick off the mark to condemn the stark gap between male and female presenters. Theresa May criticised the BBC for paying women less for doing the same job as men and Jeremy Corbyn suggested a pay cap.

How Big is the Gender Pay Gap in the UK?

Measuring the gap is tricky. Here’s a summary from the ONS of some of the key figures for the UK in 2016:

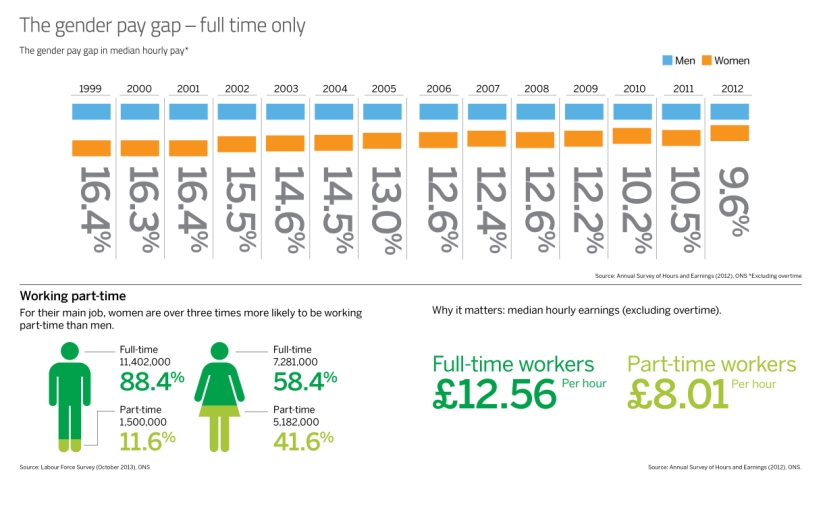

- Average pay for full-time female employees was 9.4% lower than for full-time male employees (down from 17.4% in 1997).

- The gap for all employees (full-time and part-time) has reduced from 19.3% in 2015 to 18.1% in 2016 (down from 27.5% in 1997).

So the gap is nearly 10% or 18% depending how you measure it. This FOI request shows how the gap has altered in the past decade or so in the UK. The pay gap is high, and higher than the UK, in many other parts of the EU, where the UK sits about seventh from the top: ‘across Member States, the gender pay gap varied by 21 percentage points, ranging from 5.5 % in Italy and Luxembourg to 26.9 % in Estonia’. To get some sense of the scale of the problem, in 2015 ‘women’s gross hourly earnings were on average 16.3 % below those of men in the European Union (EU-28) and 16.8% in the euro area (EA-19)’.

So what’s being done?

Something, finally. Successive governments have been determined to open up gender pay. Gender pay transparency is actually a Labour policy from long ago in 2010. Theresa May’s sound and fury has been heard before. Back in 2010 a certain Theresa May, writing in the Guardian no less, already claimed she was ‘clearing a path towards equal pay’ in 2010.What she forgot to say was that the Conservative-Liberal coalition she was part of didn’t actually engage the requirement to publish gender pay, contained in section 78 of (Labour’s) Equality Act of 2010. They wished to pursue a ‘voluntary scheme.’ Alas, few volunteered. Four years into the scheme only 4 companies had reported.

David Cameron, in a second wind of revolutionary ardour, committed to engage mandatory reporting (5 years after not doing so). This would ‘eradicate gender pay inequality’. All companies over 250 employees would have to publish the data. As of April 2017 companies have a year to produce the data and a written statement explaining, if there is a gap, what action will be taken. After 2018 organisations not publishing will be contacted by the Equalities and Human Rights Commission. The light of transparency will, it is hoped, end pay inequality.

How’s it going so far?

Although a number of companies have been voluntarily publishing the data, as of May 2017 only 7 companies had reported. An email from the GEO from July informed me there were now 26 and, according to a spreadsheet on data.gov.uk, there are now 40.

That’s from an with 250 or more employees. On a very generous rounding up, that means only 0.57% companies have reported. At this rate, if the Equalities and Human Rights Commission must send out notices next April, they’d better fire up the old email wizard or buy plenty of stamps.

There is also concern over the coverage of the policy, as this paper argued:

Only around 6000…of the 4.7 million businesses in the UK have more than 250 employees. Thus, around 59% of employees would be unaffected by the provisions if reintroduced in their current form.

The government calculated that the pay gap reporting would with a further 12% covered by regulations for public bodies, meaning ‘approximately 8,500 employers, with over 15 million employees’ would be opened up.

The argued that the data needed to be broken down by age and status, and applied to companies with less than 100 employees-moving to 50 in the next two years (the government smaller businesses may find it ‘difficult to comply due to system constraints’). May appeared to promise further action on gender pay before the General Election and there was a mention of but, like much in that doomed document, we’ll probably never know what, if anything, was intended.

What will publication do?

On a practical level much may depend on how the data is published and who accesses or uses it. Underneath this is a serious question for all transparency policies: what exactly will publication do? While opening up such data is useful, measuring gender inequality is highly complex and a ‘moving target’ and is caught within wider issues of female representation in . There is a long way between publishing data on a problem and ‘eradicating’ it.

In the case of the BBC, the controversy has led to a and high profile lobbying but will it lead to real change? Tony Hall has set a deadline for action (2020) and promised representation and consultation. Now FT journalists may strike over it and Sheryl Sandburg has weighed in.

The former Secretary of State for Equalities spoke of how publication of gender pay gaps would have benefits in terms of ‘transparency, concentrating the mind and helping people make employment decisions’, all of which are either a bit tautological (transparency will make everything more transparent) or vague. More worryingly, a survey for found that many business were unconvinced ‘44 per cent of those making hiring decisions say the measure introduced last April will not lead to any change in pay levels’. In the 2016 the Women and Equalities Select Committee that pay publication focuses attention on the issue but is not a solution: ‘It will be a useful stimulus to action but it is not a silver bullet’ and recommended that ‘the government should produce a strategy for ensuring employers use gender pay gap reporting’.

As the committee put it, openness is ‘a first step for taking action rather than an end in itself’. It is hoped that publication could drive up pay and standards-though the evidence of what publishing pay generally does is rather mixed (publishing executive pay appears to push overall pay ). Companies could be embarrassed into action but could, equally, ignore it, wait for the storm to blow over or kick it to the long grass with a consultation.

As with all sorts of openness, mandating publicity is only the start. Gender pay data must not sit on a spreadsheet but needs to wielded, repeated and find a place as a staple, symbolic benchmark-and become, like the ‘scores on doors’ restaurant star rating, a mark of quality or reason to avoid.

Images from UK government equality report and EU gender pay gap pages